Chapter 6

4 minutes

Clearbit’s story: why redefine an ideal customer profile?

At Clearbit, we had always considered top-line growth to be our #1 company metric. "Growth solves all problems" is a common refrain for many SaaS companies. For the last six years, and following a Series A raise in year five, we'd been growing rapidly with an "all you can eat" approach to leads: as long as a demo request fit within our loose ICP definition, sales spoke with them.

But when we looked at our revenue in terms of renewal, expansion, and lifetime value — i.e., the revenue we were bringing in after the close — we saw a truly surprising picture.

We found that the Pareto principle holds true for us: around 86% of Clearbit's long-term revenue comes from around 18% of the leads that enter our funnel. In other words, we had been spending too many resources on the 82% of leads that didn't show much long-term revenue impact.

The 18% of leads in the high-revenue group turn into healthy customers getting outsized value from Clearbit; they renew their annual subscriptions and increase their spending with us as time goes by. When we zoom in on the performance of this segment, we have the makings of a remarkably efficient SaaS company with metrics that match or exceed those of B2B SaaS unicorns.

We realized that our sales and marketing teams could stay lean and increase their impact if they focused on these high-LTV leads. So we redefined our ICP — we call it an "LTV ICP" — and narrowed down our universe.

We significantly narrowed our target customer at Clearbit when we redefined our ICP to maximize retention.

We significantly narrowed our target customer at Clearbit when we redefined our ICP to maximize retention.This was a big perspective shift for us. Like many of our peers, we'd been measuring our performance by quarterly net-new ARR. All that mattered was top-line revenue growth.

Of course, we also invested in customer success teams and retention programs, to grow accounts after they close. But at a high level, top-line growth was our ultimate metric. It was how we reported our success to investors, benchmarked against our competitors, and incentivized our sales teams. It provided the data around which we built our company models — models like our original ICP.

"And what's wrong with that?" you might ask. "Why not just sell to anyone, while also investing more into healthy customers? Dollars are dollars, right?"

It's a fair question, but the issue is company efficiency. If some customers don't get enough value from Clearbit, we spend a lot of time and resources up front to close them but we don't recoup our investment.

Instead, we wanted to sell to customers who love us, renew, and expand.

Flipped on its side, this funnel becomes the "bow tie model" for SaaS, described by Jacco van der Kooij as an adaptation from the original bow tie model in the airline industry, where ancillary sales after the ticket purchase (like seat upgrades) became a big business.

Our previous ICP: Built to drive top-line growth

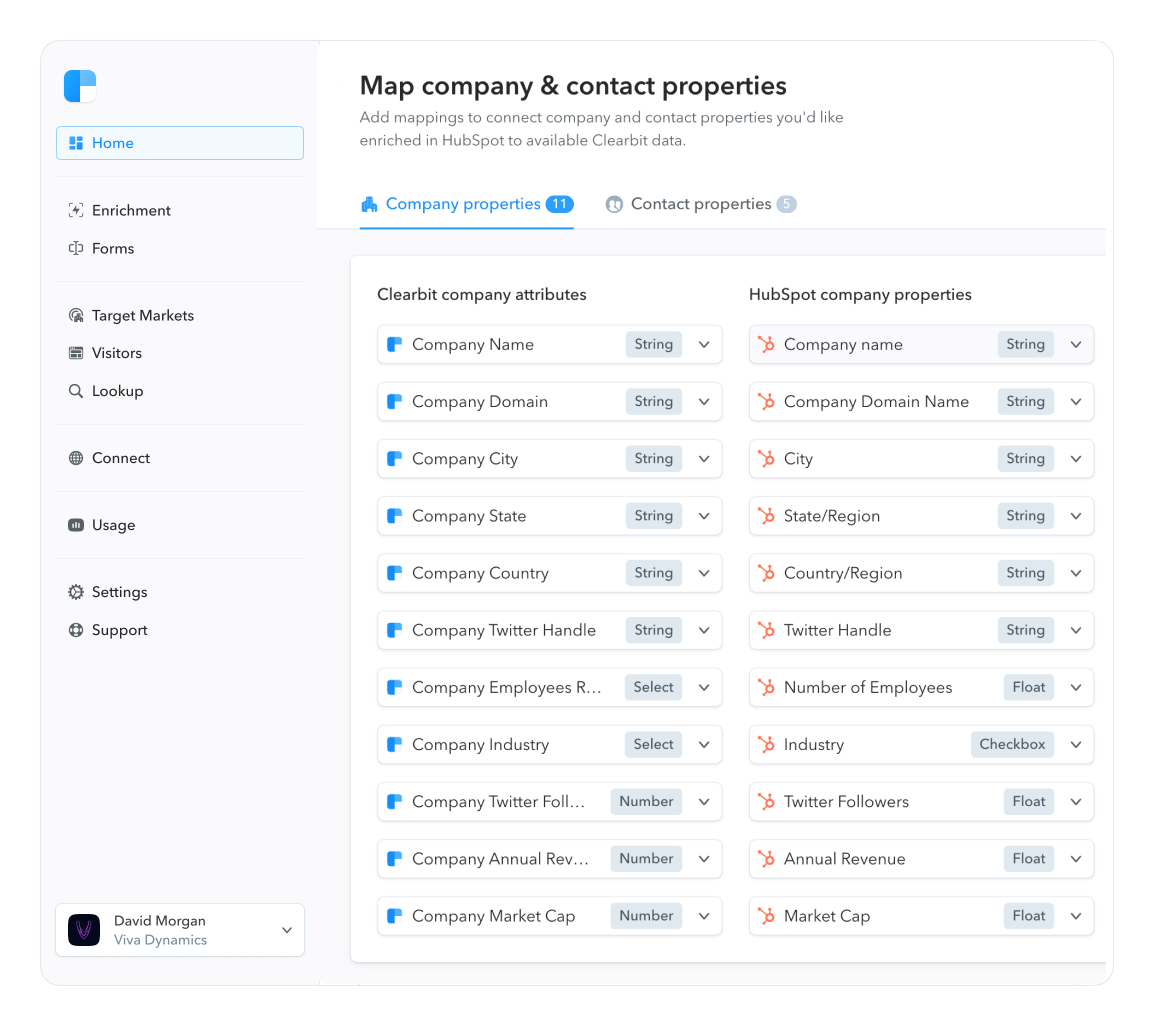

The ideal customer profile we had been using up until early 2020 was designed to maximize top-line growth, based on what worked in the past. We'd drawn up a list of all Clearbit customers and found their shared firmographic characteristics, such as:

- Number of employees (a.k.a. company size)

- Type (B2B SaaS companies)

- Country (the USA)

- Martech and BI technologies used (such as Marketo, HubSpot, or Google Analytics)

But this ICP simply mirrored all our closed/won opportunities. And Clearbit has been 100% inbound-driven for most of its existence, so we'd call this an "inbound ICP." It was based on folks who had knocked on our door, and therefore it directed our sales teams to talk to people who looked like the people who'd been coming to us. We didn't take a step back and think about the types of companies we wanted to pursue in our next phase of growth.

Our old ICP gets credit for narrowing our universe and making it more manageable. It let us automate many sales and marketing processes, like fast-tracking the highest-value inbound leads, or using the Reveal Loop to notice and recapture high-value website visitors. It guided us as we positioned our products and narrowed our ad spend through better targeting.

But in 2020, as soon as we started prioritizing "healthier" revenue from customers who landed and expanded, we needed a new, narrower ICP.